Why Europe Still Can’t Handle Elon Musk — and How Germany Killed Its Own Liberty 500 Years Ago

In December 2024, the European Commission threatened Elon Musk with fines of up to six percent of X’s global revenue. The official charge: his platform spreads „disinformation.“ The real message: No individual should wield that much power. Not in Europe. Not without permission from the authorities.

This reaction isn’t new. It’s 500 years old.

And understanding it requires a journey to a small trading town in southern Germany, near the Alps — where ordinary people once drafted the first declaration of human rights since the Magna Carta.

A Spring Day in Memmingen, March 1525

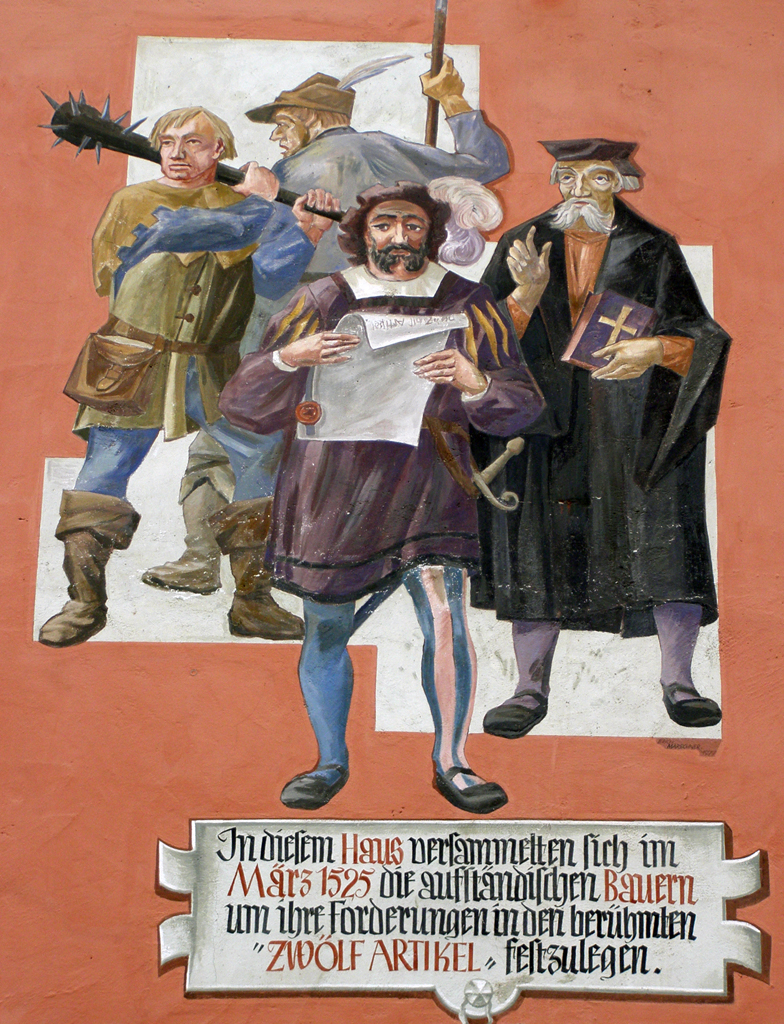

On March 6, 1525, about fifty men crowded into the guildhall of the Kramerzunft at the Wine Market in Memmingen, a prosperous town in Upper Swabia (today’s Baden-Württemberg). They were delegates from villages and communities across the Allgäu region, from Lake Constance, and from the surrounding countryside. Men with calloused hands who normally plowed fields, herded cattle, or mined salt. Now they sat at tables negotiating the future.

What they agreed upon would go down in history as the „Twelve Articles of the Peasantry“ — the first written document since the Magna Carta of 1215 to systematically demand human rights and freedoms.

A furrier named Sebastian Lotzer had written down the demands. He was no scholar, no nobleman, no clergyman. He was a craftsman from Horb am Neckar who had come to Memmingen during his journeyman years and married a local merchant’s daughter. His closest ally was the reformist preacher Christoph Schappeler, who thundered against unjust tithes from the pulpit of St. Martin’s Church.

What did these men demand? Not revolution. Not the abolition of nobility. They wanted to elect their own pastors. They wanted to gather wood from the communal forest, „as has been customary since time immemorial.“ They wanted the tithe to support the poor, not the bishops‘ splendor. And most importantly, in Article Three, they demanded the end of serfdom — because Christ had redeemed all people with his blood, „the shepherd as well as the highest, none excepted.“

Within two months, 25,000 copies of the Twelve Articles were printed. From Strasbourg to Breslau, they spread like wildfire. For the first time in German history, ordinary people had formulated their demands in writing and distributed them en masse. The printing press became a weapon of freedom.

Germany’s current President, Frank-Walter Steinmeier (a ceremonial but symbolically important role), honored this historical significance on March 15, 2025, in Memmingen: „Sebastian Lotzer, Christoph Schappeler, and the peasants who wrote freedom history here in Memmingen belong on the map of our national memory.“

A touching gesture — and simultaneously a masterpiece of symbolic distortion. Because what Steinmeier celebrates as „freedom history“ was a communal revolution from below: villages and small towns rising against centralizing authorities to demand genuine self-determination. A movement that didn’t fail because its demands were excessive — but because it threatened the princes and their monopolies.

Eight months after his Memmingen speech, the same president showed what „freedom history“ means to him in the present. On November 9, 2025 — Germany’s most significant memorial day — he delivered a speech that leading opposition figures criticized as partisan and divisive. A prominent legal commentator summarized Steinmeier’s message: „We will fight you with all means!“ The target: the opposition. And the head of state himself concluded with the words: „Let us do what must be done!“

It’s the same logic that struck the common man in 1525: The authorities honor the freedom movement — as long as it’s been dead for 500 years. The living opposition gets fought.

Imagine a U.S. President using the anniversary of Lexington and Concord to warn that today’s populists must be fought „with all means.“ That’s the closest equivalent to what Steinmeier did on Germany’s most sacred memorial day.

The Steinheimer: A Village Story

Before the great armies marched, before the blood flowed, there were people like the villagers from Steinheim near Memmingen. On February 15, 1525, about 25 representatives from villages belonging to the imperial city appeared before Memmingen’s city council. They came without weapons. They came with a request.

The city clerk Georg Meurer recorded their words. They wanted a pastor who preached the Gospel. They wanted communion in both kinds — bread and wine, not just bread. And they wanted „a patch of forest“ — as had been customary since their grandfathers‘ time.

This wasn’t revolution. This was the modest request of villagers who simply wanted to live as their grandparents had lived, before the lords invented ever new taxes and privatized ever more communal land.

The Memmingen council responded surprisingly accommodatingly. It made concessions. It negotiated. For a brief moment, it seemed the conflict might be resolved peacefully.

It would turn out differently — but not because the villagers wanted it that way.

The Trap: How the Princes Weaponized Negotiations

To understand why what was later called the „Peasants‘ War“ escalated so brutally, you must grasp a perfidious strategy that’s largely forgotten today: The princes and cities systematically used negotiations to identify the leaders of the uprising — and then targeted them for elimination.

The pattern was almost always the same: A band of insurgents besieges a town or castle and demands acceptance of the Twelve Articles. The besieged side requests negotiations and guarantees safe conduct for a delegation. The insurgents send their spokesmen — often preachers, scribes, captains — who come in good faith. Once names and faces are known, the guarantees are broken. Either the negotiators are arrested immediately — despite guaranteed safe conduct. Or they’re allowed to leave initially and seized in the following days, because now the authorities know exactly who the „ringleaders“ are.

The princes called this openly „cutting off the heads.“ In their letters, this phrase appears again and again. The Truchsess of Waldburg put it this way: „One must identify the ringleaders, and the others will then be quiet.“

The most famous example is the Treaty of Weingarten from April 17, 1525 — the largest „treaty“ of the entire so-called Peasants‘ War. The Swabian League invited the Upper Swabian bands to negotiations. The insurgents sent their captains and preachers, trusting the guarantees. The treaty itself was even favorable to them. But in the following weeks, dozens of the captains and preachers who had appeared were systematically arrested and executed — despite having been guaranteed safe conduct.

The word spread. Of course it spread.

The Escalation: What Choice Did the Insurgents Have?

Anyone who wants to understand the violence of the 1525 revolution must understand this systematic perfidy of the opposing side. The insurgents learned quickly: Whoever negotiates, betrays themselves. Whoever shows their face is condemned to death. Whoever trusts guarantees is lost.

Traditional historiography portrays it as if „radical“ leaders escalated the conflict. But the question must be: What other choice did they have?

When every negotiation becomes a trap, when every safe conduct is broken, when the authorities systematically lie and murder — then only fighting remains. Not because the insurgents wanted violence. But because every other path was cut off from them.

Thomas Müntzer: A Man Without Alternatives

About 250 miles northeast of Memmingen, in the small town of Allstedt in the Südharz region, Thomas Müntzer preached. Born around 1489, he was a theologian who had studied at Leipzig and Frankfurt an der Oder, initially a fervent follower of Martin Luther. But while Luther admonished the peasants to obey worldly authority, Müntzer took a different path.

„Christ was born in a stable,“ he preached. „He stood on the side of the poor and disenfranchised. The princes, clothed in furs and sitting on silk cushions, are an abomination to Christ.“

On May 15, 1525, about 8,000 poorly armed people — peasants, miners, craftsmen — met the army of the united princes at Frankenhausen. It wasn’t a battle. It was a massacre. At least 6,000 people were slaughtered. The mercenaries drove the fleeing before them and cut them down like cattle.

Müntzer was captured, tortured, forced to recant his „errors.“ On May 27, 1525, he was beheaded outside the gates of Mühlhausen. His head was placed on a pike and displayed as a warning.

His wife Ottilie, a former nun from impoverished minor nobility, remained behind with their infant son. She had to watch as everything her husband had fought for drowned in blood. She died a few years later, presumably destitute. All trace of the son is lost.

The Victor’s Justice

Nearly 100,000 people died in a few weeks — three percent of the population in the uprising areas between Tyrol and Thuringia. But the killing didn’t stop when the battles ended.

The Swabian League itself reported executing about 10,000 people in southern Germany. Many more suffered torture, blinding, the chopping off of fingers or hands. In Nuremberg, the heads of the executed were placed between their legs — to deny them eternal salvation.

In Würzburg, sixty-six peasants and townspeople were beheaded on a single day, June 8, 1525 — many of them identified as negotiators.

„The transition from massacre to victor’s justice was fluid,“ writes the literary scholar Peter Seibert. „The common man was so thoroughly beaten and thrown back to the status of the defeated that he could not inscribe himself as a victim in cultural memory.“

What Happened 200 Miles to the West

While in the Empire the insurgents were crushed, serfdom was even intensified east of the Elbe, and the cities were bound into guild constraints and territorial states, a completely different model was already developing just 200 miles to the west.

The northern Netherlands — Holland, Zeeland, the great trading cities — gradually detached themselves from the Empire. In 1568, the War of Independence against Spain began. In 1581, they declared independence with the „Plakkaat van Verlatinghe“ — the first modern declaration of independence in history. In 1648, the Peace of Westphalia finally recognized the Republic of the Seven United Provinces.

In this space that had catapulted itself out of the Holy Roman Empire, exactly the social model developed that never took hold in the Empire: relatively high religious tolerance, no more serfdom, strong municipal autonomy, world market orientation instead of guild compulsion, early joint-stock companies like the Dutch East India Company of 1602, a relatively free land and labor market.

The Freiburg historian Peter Blickle and later Charles Tilly and Wim Blockmans formulated it this way: „The communalism of peasants and small towns in the Empire failed in 1525. The same communalism triumphed in the same century in the northern Netherlands — because there it could no longer be crushed by the Emperor and territorial princes.“

In other words: The Dutch could actually implement what the Upper Swabian, Franconian, and Thuringian peasants and townspeople wanted in 1525 — strong communities, little central authority, freedom from arbitrary taxation — because they had catapulted themselves out of the Imperial framework.

That’s why Amsterdam (not Frankfurt, Augsburg, or Nuremberg) is considered the first truly „modern“ city in Europe from about 1580 onward.

And here’s what matters for Americans: The Dutch Republic became the model for the Founding Fathers. The ideas that were drowned in blood in Germany in 1525, that triumphed in the Netherlands, would cross the Atlantic and find their fullest expression in the United States Constitution.

The Genetic Clear-Cut

The men and women who fought for individual rights in 1525 weren’t just militarily defeated. They were systematically exterminated. Their families were impoverished. Their villages were burned. Their ideas were branded with the stigma of „rebellion“ for centuries. Whoever survived learned: Obedience is survival. Resistance is death. And above all: Never trust the authorities.

The Thirty Years‘ War (1618-1648) completed what the suppression of 1525 had begun. Forty percent of the population died. Hans Heberle, a shoemaker from Neenstetten near Ulm, noted in his diary how he and his family were „hunted like wild game in the forests.“ The survivors developed a collective survival strategy: adaptation to authority. Mistrust of anyone who questioned the system.

The Emigration of 1848

Three hundred twenty-three years later, after the failed revolution of 1848, the pattern repeated. Robert Blum, the most popular democrat of his time, was executed on November 9, 1848, in Vienna — despite his immunity as a delegate to the Frankfurt National Assembly. „Shot like Robert Blum“ became a German saying.

Carl Schurz, a young student from Bonn, fled through the sewer of the besieged fortress of Rastatt. A year later, he freed his mentor, Professor Gottfried Kinkel, in a daring operation from Spandau Prison. Then he emigrated to America.

In the USA, Schurz became a brigadier general in the Civil War and later Secretary of the Interior (1877-1881) — a career that would have been impossible in Germany. „Ubi libertas, ibi patria“ — where liberty is, there is my homeland — became the motto of the German emigrants.

The numbers are staggering: 80,000 people left Baden alone — five percent of the population. In 1854, German emigration to America reached its historical peak with 239,000 people. Not coincidentally, the conservatives called this a „cleansing.“ The liberals left. The obedient stayed.

The Thesis — A Clarification

It wasn’t a „Peasants‘ War.“ It was the Revolution of the Common Man in town and country — and it was deliberately defamed as a „Peasants‘ War“ because that’s what the victors wanted.

Of course, it would be too simple to claim the last liberals disappeared in 1525. The revolution wasn’t a purely „liberal“ movement in the modern sense. Thomas Müntzer was a religious apocalypticist, not an Enlightenment thinker. The insurgents fought for their communities, not for abstract human rights. Some demanded a return to „ancient law“ — not the creation of something new.

And yet: What was formulated in Memmingen contained the seed of what we today call liberal values. The idea that legitimacy comes from below. That rule is bound to conditions. That the individual has rights that no authority may take from them.

These ideas were defeated in the Empire in 1525 — but they triumphed in the same century in the Netherlands, because there the princes no longer had power. They were buried in collective trauma from 1618-1648. They were driven into exile in 1848. And each time, Germany was left a little poorer.

Back to the Present

What does this have to do with Elon Musk?

When the EU Commission punishes an individual because he spreads the wrong content, it follows a logic older than itself. It’s the logic of the princes who said in 1525: The common man should not decide for himself what to believe. It’s the logic of Luther, who wrote: „One must restrain the rabble with force, like a wild beast.“

The American approach — let people speak, let the marketplace of ideas decide — is deeply foreign to European elites. Not because they’re evil. But because their culture has been shaped for 500 years by the conviction that freedom is dangerous. That the individual is too stupid to make the right decisions. That it requires a wise authority to protect the people from themselves.

German polling data confirms this cultural imprint: Approval of America fell from 60 percent (1950) to 29 percent (2025). Not because of Vietnam. Not because of Trump. But because America stands for something Germany never had: a successful revolution from below.

The Unasked Question

Perhaps it’s time to ask an uncomfortable question: What if 1525 had turned out differently?

What if Sebastian Lotzer had stayed in Memmingen and the Twelve Articles had become the foundation of a new order? What if Thomas Müntzer’s head hadn’t ended up on a pike? What if the princes had kept their safe conduct guarantees instead of systematically breaking them?

Would then have developed in the Empire what developed in the Netherlands — that mixture of municipal self-governance, religious tolerance, and economic freedom that we today call „liberal“?

We’ll never know. But we can stop pretending that German skepticism toward individual freedom is a sign of maturity. It’s the echo of a 500-year-old trauma — and the legacy of an authority that systematically murdered everyone who defied it.

The Revolution of 1525 never stood a chance against the princes‘ mercenaries. But its ideas survived — in America, in Switzerland, in the Netherlands. Everywhere the exiles fled or where the princes no longer had power.

The ideas of Memmingen crossed the Atlantic with men like Carl Schurz. They found their fullest expression in a Constitution that begins with „We the People“ — the very principle that Germany’s princes drowned in blood.

The question for Germany in 2025 is simple: Will the ideas of 1525 ever be allowed to come home — or will the princes still rule from Brussels and Berlin?

This is a thesis, not the final truth. But perhaps it’s a thesis worth thinking about.

Schreibe einen Kommentar